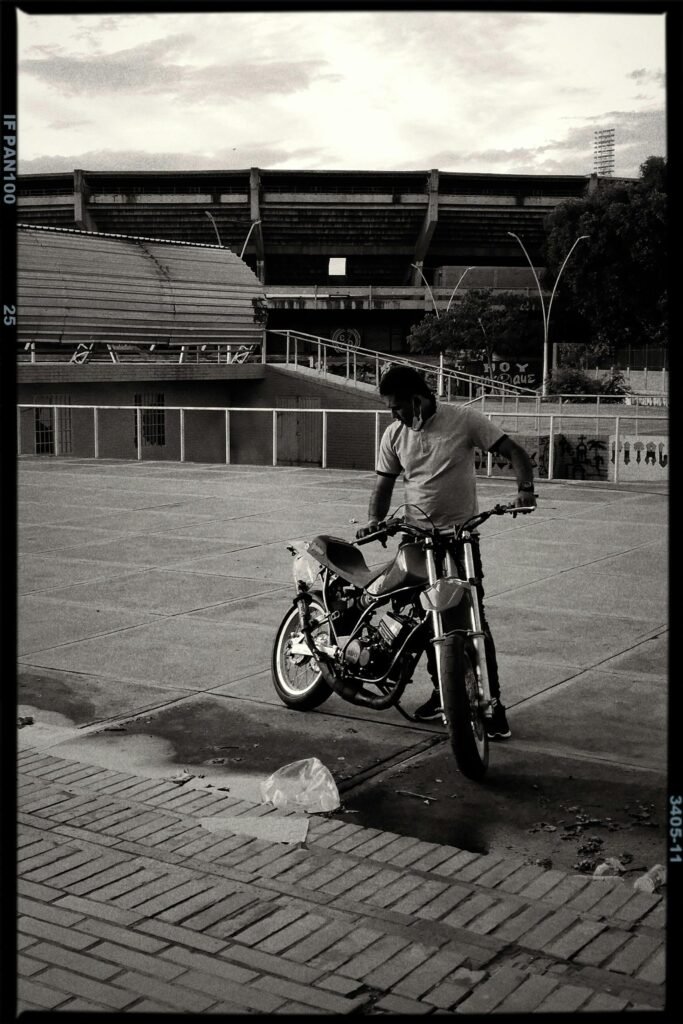

Photo Credit (Pixeles)

Directors and writers frequently use their preferred visual medium to create a tale, whether or not they practice filmmaking. Ideologies, ideas, or any other type of communication is always deciphered in this visual medium with the intention that the audience understands it. The key to creating a great film, particularly when delivering a tale, is to avoid preaching.

From Mel Gibson to Seth Macfarlane, Federico Fellini to Ridley Scott, and, of course, Hitchcock, their films convey messages ranging from symbolist narrative to cunning subtext dialogues. Here’s a list of movies with philosophical messages encoded for the viewer. Please keep in mind that the films listed below are arranged chronologically.

- Rope (1948) by Alfred Hitchcock

Hitchcock, the maestro of suspense, plays with his audience, repelling and luring them into a realm of shock. Rope is one of his most ambitious pictures, made specifically as a one-shot: a real-time experiment.

This overlooked classic stars James Stewart, Farley Granger, and John Dall. It has some of the most innovative filmmaking of its day, as well as perspectives on superior and inferior humans. The film is based on the 1924 Leopold-Loeb case, which tells the story of two homosexual law students in Chicago who murdered a 14-year-old kid for fun to demonstrate their intelligence and ability to get away with it.

This is an anti-existentialist film, and James Stewart is horrified to learn that two of his students murdered a classmate using existentialism ideas. Finally, James Stewart recognizes that following this idea causes pain for both the follower and those around him. This film has connections to Nietzsche’s ideology, “Ubermensch,” as well as Freudian undertones.

- The Fountainhead (1949; King Vidor)

This is an adaptation of Ayn Rand’s novel, a melodrama about individualism shot in a captivating German Expressionist manner. This film, starring Gary Cooper as an independent architect who strives to maintain his integrity, serves as a metaphysical statement, artistic manifesto, and criticism on American architecture, ethics, and political beliefs.

A lot of the fun comes from skilled characters trying to do their best with silly dialogue and occasionally providing the best performances. Gail Wynard, played by Raymond Massey, is an intriguing character in the plot because of the changes he undergoes during the film. Meanwhile, Gary Cooper, as Roark, is a tool, an egotistical man who struggles to adapt to public expectations.

- The Seventh Seal (1957) by Ingmar Bergman

Ingmar Bergman, known for his films Persona, Wild Strawberries, and Fanny & Alexander, created The Seventh Seal, a cinematic model of existentialism that depicts a man’s cataclysmic search for meaning. This remarkable story follows a knight who challenges Death to a fateful game of chess.

Although this film is about understanding oneself via metaphysical and philosophical concerns, the Swedish director also encourages the audience to engage with issues such as the dilemma of evil, religious philosophy, and existentialism. Bergman brilliantly depicts Bloch’s struggle with his ideas, the reality of an omnipotent God in the world, for his audience to see and evaluate for themselves.

This film raises a lot of concerns; it neither preaches nor disparages any certain group. Instead, it simply provides opposing viewpoints and allows the audience to discuss them.

- La Dolce Vita (1960; Federico Fellini)

La Dolce Vita, directed by Federico Fellini (renowned for films including 8 ½, Amarcord, Roma, and Satyricon), has a dark and frequent sense of humor about the opulent lifestyles of individuals in Rome.

Marcello Mastroianni starred in this film as a gossip writer who can’t determine what to do next and feels confined in a box. This film appears to be Fellini’s attempt to communicate with his audience about the seven deadly sins, which take place over seven crazy nights and dawns.

The entire film is set between Rome’s Seven Hills, amid nightclub streets and cafe sidewalks. If you can’t quite visualize it, close your eyes and imagine Van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night. La Dolce Vita is one of the rare films that may provide spectators with a sense of philosophy, life, and death at different points in time while they watch it. There may not be such a thing as a good life, but the decisions you make will decide it.

- My Night at Maud’s (1969; Eric Rohmer)

This film, directed by Eric Rohmer, tells the story of a young engineer (Jean) who discovers an attractive blonde woman who is also a practicing Catholic. But his entire purpose is put on hold when he runs into a friend (Pascal), who spends the entire evening talking religion and philosophy.

They both arrange to meet the next day to continue the conversation at Maud’s place. During the debates, Pascal placed a bet, offering huge odds against God’s existence of 100 to one. They all have to wager on that one chance. If God does not exist, they lose the bet, but it is irrelevant to them. But if God exists, their lives are meaningful, and the prize is eternal life.

The characters in this film are bright, confident, talkative, masters of deception, and capable of deceiving themselves.

- Love and Death (1975; Woody Allen)

Woody Allen has managed to combine his Kafkian anxiety and Kierkegaard’s fearfulness into a constant comedy about war and peace, crime and punishment, and fathers and sons.

Allen plays Boris, who couldn’t sleep without the lights on until he turned thirty. He’s set to be executed for a crime he did not commit. Throughout the film, Allen spits out humor from a variety of visual mediums, including Persona as a stylized parody, one-liners from Attila the Hun, and more.

At the end, Allen discusses love and death, what he has learned about life as a human, how our minds are great but the bodies have all the fun, how we believe God is an underachiever, and how death is somewhat depressing. This reminds us of Matthew 20:16, which states, “So the last shall be first, and the first shall be last.”

- Being There (1979) by Hal Ashby

Being There is an adaptation of Jerzy Kosinski’s 1970 novel. Peter Sellers portrays a humble gardener who has never left the estate till his boss (Ben) dies. Things get tricky when it comes to Ben’s funeral. The President and other political leaders are debating the next presidential candidate, and Chauncey’s (Peter Sellers’) name emerges as their preference.

This film embraces the moral and intellectual ramifications of television’s presence, yet in doing so, it does not upset a television-dependent public.

One component of Hal Ashby’s flair is his ability to show something amusing while never losing sight of the film’s gravity or presenting the humanity of the characters. He had previously made outstanding films such as Harold & Maude and The Last Detail, but this is a satirical comedy film that will leave you with a lot of inspiration and thoughts regarding Heidegger’s philosophy.

- My Dinner with André (1981; Louis Malle)

Andre Gregory and Wallace Shawn starred in and authored the script for this film, which follows two men enjoying dinner in a luxury restaurant and discussing life. Yes, this is the complete plot. Even with a basic plot, their chats are nevertheless thought-provoking.

This dispute is primarily about Andre’s spiritualistic and idealistic perspective versus Wallace’s pragmatic humanism and practical-realistic worldview. Andre and Wallace are two distinct men, one crazy and the other a settled type.

This film is regarded as a cult classic among independent film critics and filmmakers for its philosophical meaning and minimalist style, as well as its deep discussions about life, the human condition, religion, and communication. The brilliance of this film is that it is simultaneously correct and incorrect.

Andre and Wallace became personally and emotionally interested as the chats progressed, communicating on a level that exceeds most kinds of sociability. This film provides the most accurate portrayal of human communication in a visual medium.

Leave a Reply