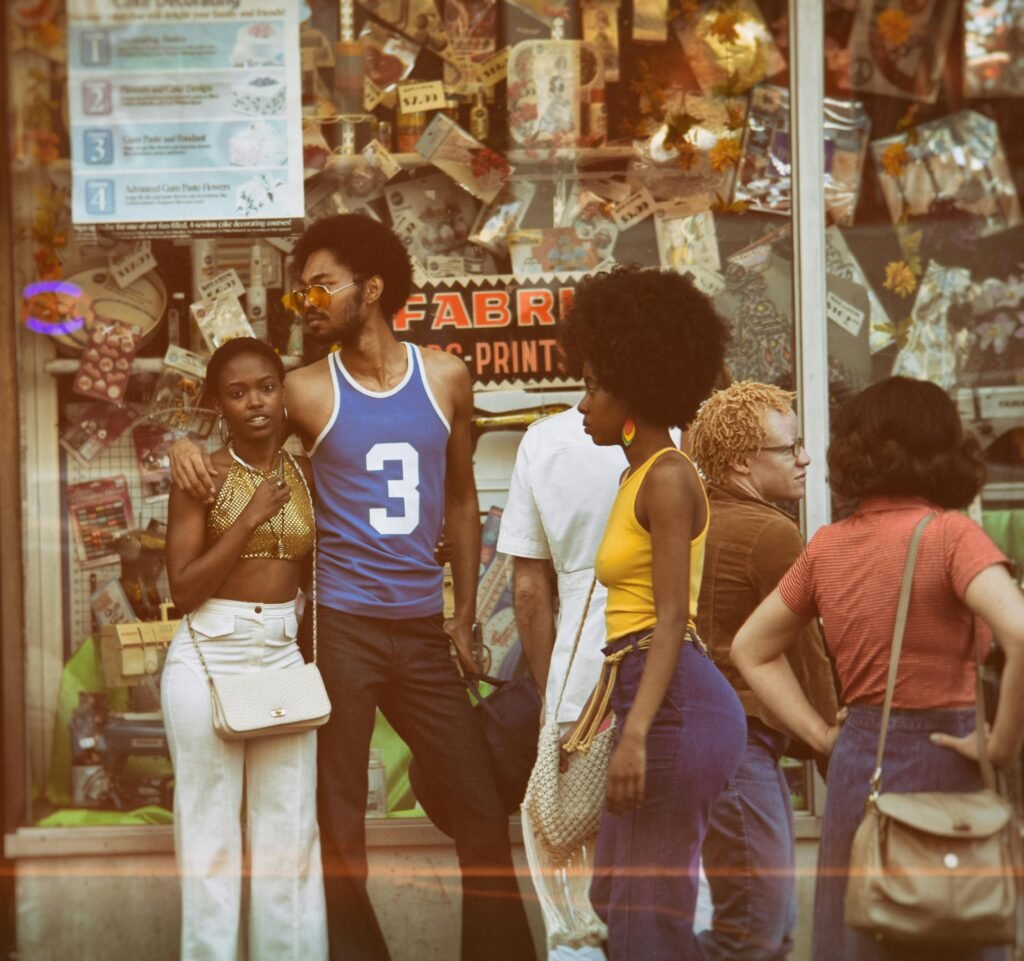

Photo Credit (Gettyimages)

Unquestionably, the New Hollywood boom of the 1970s produced certain masterpieces that have stood the test of time and deserve our utmost respect. In spite of this, it is inarguable that that era of cinematic history contains many more underappreciated treasures than critically acclaimed masterpieces. There are countless underappreciated masterpieces buried in history for every Godfather. Even though it’s frustrating when our favorite films don’t receive the recognition they deserve, there’s joy in delving into that era and uncovering its hidden treasures.

Most movie lovers could probably think of a thousand underappreciated American films from the ’70s if asked. First things first, though: these are ten major gaps. belonging to the officially sanctioned classic subset.

- A Haven of Safety (1971)

A Safe haven, written and directed by Henry Jaglom, is about a young woman named Noah (Tuesday Weld) who, while living on her own in New York, remembers “her safe place” from her youth. She goes through two relationships, one with the cool and contemporary Mitch (Jack Nicholson) and memories of an enigmatic street magician she met when she was a kid (Orson Welles, superb).

Packed with breathtaking visuals, the film takes viewers on a gloomy and imaginative journey into Noah’s (or Susan’s) mind. It seems like Jaglom’s film was assembled from fifty hours of filming; it’s soulful and unadulterated. His protagonist is a loner from the flower child generation, yet the picture succeeds when it departs from the formula of the ’70s. Thanks to Jaglom’s vision, the film looks utterly contemporary; no one could ever classify it as one of the more dated features from the ’60s and ’70s.

She gives what is arguably her most unrestrained and assured performance to date in the picture, and it’s fantastic. As a result of Jaglom clearing the way, she was able to make an absolutely breathtaking effort. The work that Weld does in this picture is more akin to an existence than an act. Jaglom gives her the freedom to be imaginative and carefree, and she possesses a touch of femininity despite her childlike nature. Weld does a good job of keeping the picture together, but Orson Welles steals the show. In fact, he is fantastic, and I consider it to be among his best acting performances for a different filmmaker. Having the opportunity to direct Welles—a filmmaker he had long admired—for Jaglom’s debut feature was a lifelong goal.

Despite its critical and commercial failure, A Safe Place has, like much of Jaglom’s other films, developed a devoted fan base among feminists. In my opinion, it is a risky yet thrilling form of introspective filmmaking that very few directors would dare attempt in the modern day. “It’s a film about the loss of innocence,” Jaglom subsequently explained. “About the killer app that is dwelling on the apparently beautiful past and how it prevents you from living in the present and functioning for the future.” A lesson from which I think we can all benefit.

- Wonderland’s Alex (1970)

Paul Mazursky’s Alex in Wonderland (1970), a Fellini-esque self-referential look at the filmmaker’s life and daily challenges, is a fascinating but underappreciated picture. Donald Sutherland, who rose to fame with parts in seminal films like MASH and Kelly’s Heroes, plays the lead role of Alex with impressive control and reliability. Despite playing a character who is artistically insecure, his presence gives the film the grounded quality it needs, which is especially important considering there is no plot to keep things together. Still, it’s a blast from start to finish because of Mazursky’s lighthearted directing and Sutherland’s charisma.

It also had Fellini’s unforgettable appearance, made just a few years before he cast Sutherland as Casanova in his own film. Sutherland later admitted to being completely inappropriate for the role of Alex and also said that he had declined the lead role in Straw Dogs, directed by Sam Peckinpah, so he could collaborate with Mazursky. (One of the great what-ifs in cinematic history features Sutherland as the mathematician turned primal male in Straw Dogs.)

Mazursky, like Henry Jaglom, is a neglected but crucial figure from the New Hollywood boom. If you enjoy character-driven American films, you should definitely check out this treasure.

Thirdly, in 1970, I Did Not Sing for My Father

The role that turned Gene Hackman’s career around was in I Never Said For My Father (1970), for which he received his second Academy Award nomination. Gilbert Cales developed it from his own successful play, and Gilbert Cates directed the film. The film stars Gene Garrison (Hackman), a college professor and widow who is overshadowed by Melvyn Douglas’s tyrannical father, Tom.

As the film opens, Gene is “enjoying” a night at home with his parents, but he can’t help but think of his dad’s relentless teasing. Much to Gene’s dismay, he ends up spending more time with his dad after his mother’s heart attack and subsequent death puts him in the hospital. Concurrently, Peggy, Gene’s fiancée, begins to develop feelings for Tom, the elderly guy, and Gene plots to remarry and escape from his past. The younger man experiences debilitating inner problems as a result of this.

Like most films of the time dealing with existential crises, the storyline summary of I Never Said For My Father does not give a true image of the film. Similar to Five Easy Pieces, another depressing drama from the same year that deals with parental issues, the performances, conversations, and tension between the main characters are the show-stoppers. Hackman gives the film its distinctive flavor with an understated, multi-layered performance in which he communicates more through silences and gestures than through the words he chooses to use. Behind the surface, there is affection for his father; the issue is in expressing it. But Hackman is an actor who isn’t afraid of a challenge, and he does it with elegance and beauty.

I Never Sing For My Father is probably unknown to everyone but Hackman’s most ardent fans and has long since been forgotten. A fair re-evaluation and re-release are in order.

- 1972’s Prime Cut

Gene Hackman kept busy post-Oscar triumph, when he won best actor for The French Connection. While some were more cerebral (like Poseidon Adventure), others were huge hits with audiences. Among his early to mid-1970s films, Prime Cut (1972) regrettably receives less attention than some of his others. Michael Ritchie’s film tells the story of Nick, played by Lee Marvin, as an enforcer dispatched from Chicago to collect £500,000 owed to the menacing “Mary Ann” (Hackman), a magnate in the Kansas City meat industry. However, this is not your average mobster shootout.

A dark subplot involves Nick rescuing a young girl (Sissy Spacek) from Mary Ann’s human sex slave sale, in which the teenagers are nabbed and sold to the highest bidder; there are also indications of homosexuality between Mary Ann and his deranged brother. Adding insult to injury, it is established right from the beginning of the film that Mary Ann has orchestrated the dismemberment and processing of one of the guys from the Chicago mafia into sausage.

To say that all of this contributed to the film’s controversy in 1972 would be an understatement. Despite the unpleasant aftertaste, it is daring, well-acted, and well-made. The writing is so good that the time flies by, and there is a lot of memorable conversation. Compared to our more primitive companions who are purchased, sold, and processed, there is a statement being made here on the concept of meat, which is defined as dead flesh, the price of flesh, and the value of humans. Still, it’s mostly just a thrilling, engaging thriller. As Mary Ann, a creep who carelessly runs his empire and is indifferent with the world outside his seedy sphere, Hackman is utterly vile, in contrast to Marvin, the sturdy hero.

- The Brothers Dion (1974)

The Dion Brothers, sometimes called The Gravy Train, is an obscure classic whose relative obscurity is rather puzzling. The film is nearly hilariously funny from beginning to end, and it was directed by Jack Starrett and co-written by Terence Malick and David Whitney.

As Stacy Keach and Frederic Forrest’s Calvin and Rut, respectively, traverse the United States on their naughty criminal adventures, the show follows them. The two former coal miners quit their employment and agree to assist in an armed robbery. The heist goes smoothly at first, but it is later shown to have been staged so the Dions will be blamed while Tony (Barry Primus) and Carlo (Richard Romanus), the ringleaders, escape. However, don’t underestimate the Dions’ wit. After escaping an ambush in which they were dressed as police officers, they set off on a mission to exact retribution, vowing to find the weasel responsible for abandoning them for dead.

The writing is filled with urban humor and nail-biting situations, and it’s just plain funny. Also, the acting is top-notch. Keach plays the role of the calm, mustachioed older brother—a cunning con artist who keeps his cool under pressure—while Forrest plays the role of the naive, impulsive puppy. Even if you’re engrossed in the events unfolding onscreen, the picture flies by at a breakneck pace, thanks to the charming chemistry between the leads.

Despite its dismal reception upon its initial release, the film has happily gained a cult following over the years; Quentin Tarantino is one such enthusiast who even considered remaking the film. “Everyone on the fucking planet should watch this movie; it’s a classic!” Guillermo Del Toro gushed about it once, proving that even he adores it.

Unfortunately, there has been no official physical release of the picture, despite its reputation as a cult classic. It would be great if it were released on Blu-ray with all the extras at some point.

Leave a Reply